When I noticed that Steve Cerra over at the always interesting blog titled Jazz Profiles had posted a tribute to artist illustrator David Stone Martin, one of the absolute heroes of Jazz record jacket art, I figured something fine was awaiting anyone who linked in. And I was right. Go to Cerra's complex and inventive site here to get hooked in (and I do mean "hooked").

As a Jazz LPs collector and an Internet books/records seller as well, I've long been a fan of DSM's cranky, crafty, creative line work.

I've sold collectable samples (record jackets, magazines with his illustrations, books with jackets and interior art) for about 20 years now, and I still always find something crazily new to admire. Cerra's DSM visual samples, set to a baritone sax workout, are somewhat chronological; from the early Moses Asch days, through his decade-and-more yeoman's work for Norman Granz's Clef/Norgran/Downhome/ Verve labels, to his later work for more obscure employers, DSM typically delivered a drawing that was off-the-wall, intriguing, and caricature-based.

I've sold collectable samples (record jackets, magazines with his illustrations, books with jackets and interior art) for about 20 years now, and I still always find something crazily new to admire. Cerra's DSM visual samples, set to a baritone sax workout, are somewhat chronological; from the early Moses Asch days, through his decade-and-more yeoman's work for Norman Granz's Clef/Norgran/Downhome/ Verve labels, to his later work for more obscure employers, DSM typically delivered a drawing that was off-the-wall, intriguing, and caricature-based.  And after all these years, and studying the few admiring books that feature the artist, and even discovering a couple of obscurities myself, I still must admit that I'm familiar with only two-thirds of the images shown in Cerra's tribute, meaning the ones I've personally owned and/or sold.

And after all these years, and studying the few admiring books that feature the artist, and even discovering a couple of obscurities myself, I still must admit that I'm familiar with only two-thirds of the images shown in Cerra's tribute, meaning the ones I've personally owned and/or sold.The very expensive "standard" work on the illustrator (selling for $250 and up at present) is an oversize, limited-edition paperback that appeared only in Japan back in 1991, dedicated collector Manek Daver's Jazz Graphics: David Stone Martin, offering about 200 samples of his work, mostly Jazz album covers and other line drawings.

But DSM had a long and distinguished career apart from Jazz too. Around 1933, a young art school grad still living in Chicago, he became an assistant to the great, politically committed artist Ben Shahn, who was painting a mural for the upcoming Chicago World's Fair; and after that effort Shahn's contacts in the Roosevelt government helped DSM become art director for the Tennessee Valley Authority for the rest of the decade. Shahn and DSM also reunited during WWII when both worked for the OSS and then OWI. (One might also note that Shahn and his short-term protege

But DSM had a long and distinguished career apart from Jazz too. Around 1933, a young art school grad still living in Chicago, he became an assistant to the great, politically committed artist Ben Shahn, who was painting a mural for the upcoming Chicago World's Fair; and after that effort Shahn's contacts in the Roosevelt government helped DSM become art director for the Tennessee Valley Authority for the rest of the decade. Shahn and DSM also reunited during WWII when both worked for the OSS and then OWI. (One might also note that Shahn and his short-term protege  shared certain charac-teristics in their line- drawing styles and socially- conscious subject matter.)

shared certain charac-teristics in their line- drawing styles and socially- conscious subject matter.) DSM then moved on to a freelance designer/illustrator career in New York, and began supplying drawings to magazines. Thanks to pianist Mary Lou Williams, he was soon also hired to provide a variety of cover illustrations for 78 rpm albums on Asch and Disc and Stinson, with subjects ranging from Square Dancing to Calypso, Prokofieff to Leadbelly, Richard Dyer Bennett to James P. Johnson.

But when Norman Granz launched his jam session-styled concerts in Southern California, soon called Jazz at the Philharmonic,

and then licensed the early concert tapes to Asch's labels, Granz and DSM quickly discovered they had like interests and similar quirky attitudes... And there was no turning back after that. Hired to work for ever-contentious Norman in 1947 (who was starting his own Clef Records), over the years the artist drew hundreds of LP jackets and other illustrations, from program booklet covers to label designs, with famous and sometimes fractious images of Charlie Parker, Oscar Peterson, Lester Young, Benny Carter, Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Johnny Hodges (nicknamed "Rabbit"), Bud Powell, Art Tatum, and many other heroes of the Mainstream and BeBop Fifties. But likely the best remembered later were his many drawings for releases by Billie Holiday, and the umpteen versions of wildly popular JATP performances.

and then licensed the early concert tapes to Asch's labels, Granz and DSM quickly discovered they had like interests and similar quirky attitudes... And there was no turning back after that. Hired to work for ever-contentious Norman in 1947 (who was starting his own Clef Records), over the years the artist drew hundreds of LP jackets and other illustrations, from program booklet covers to label designs, with famous and sometimes fractious images of Charlie Parker, Oscar Peterson, Lester Young, Benny Carter, Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Johnny Hodges (nicknamed "Rabbit"), Bud Powell, Art Tatum, and many other heroes of the Mainstream and BeBop Fifties. But likely the best remembered later were his many drawings for releases by Billie Holiday, and the umpteen versions of wildly popular JATP performances.  And DSM's very clear signature on every cover no doubt helped him land other work--a few children's books, graphic design jobs, many cover paintings for Time Magazine, Broadway show posters, later film and television design credits, even a couple of Jazz related books: Mister Jelly Roll, the as-told-to autobiography of Jelly Roll Morton assembled by Alan Lomax from copious tapes, and nearly two decades later the many drawings for an early-years history of the Monterey Jazz Festival, called Dizzy, Duke, the Count and Me. (Most of the Morton drawings, by the way, also showed up individually, recycled as non-Jelly Roll jacket illustrations a couple of years later. Maybe the artist retained his copyrights?

And DSM's very clear signature on every cover no doubt helped him land other work--a few children's books, graphic design jobs, many cover paintings for Time Magazine, Broadway show posters, later film and television design credits, even a couple of Jazz related books: Mister Jelly Roll, the as-told-to autobiography of Jelly Roll Morton assembled by Alan Lomax from copious tapes, and nearly two decades later the many drawings for an early-years history of the Monterey Jazz Festival, called Dizzy, Duke, the Count and Me. (Most of the Morton drawings, by the way, also showed up individually, recycled as non-Jelly Roll jacket illustrations a couple of years later. Maybe the artist retained his copyrights?  Well, Granz for sure would have appreciated a slightly-used work at a bargain price!)

Well, Granz for sure would have appreciated a slightly-used work at a bargain price!) DSM worked for Granz until the Sixties when the producer sold his labels and "retired" to Switzerland. I suppose the artist illustrator at first maintained his career full steam, but aside from a couple dozen jackets for other small independent labels and the Time covers, plus drawings commissioned by fans, his later career is a bit of a blank. He suffered a stroke in the Seventies, and--to be blunt rather than polite--his illustrations became less inventive and more distorted, even desperate. But he is of course remembered and revered for all the great ones.

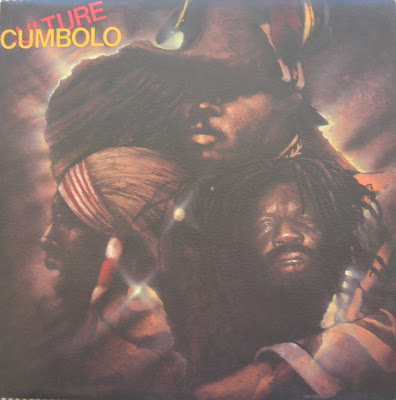

I've added several less-known pieces as illustration examples for this brief addendum to Cerra's tribute, most of them missing from his selected visuals, but a couple of them rare enough to be absent from Daver's book--a somewhat stodgy mural painted for the TVA; a 78 Folk album Daver missed, and a Granz-era surprise (who knew Al Hirt got a DSM look-in?); an illustration from a children's songbook (more rabbits!) showing the artist's simpler side, along with a drawing of Jelly Roll so detailed and distinct from the artist's usual sketchy, often surreal style, that it might stand in for those long-forgotten Time covers too; plus some other LP jackets missing from one source or the other (like the beautiful scene up top

I've added several less-known pieces as illustration examples for this brief addendum to Cerra's tribute, most of them missing from his selected visuals, but a couple of them rare enough to be absent from Daver's book--a somewhat stodgy mural painted for the TVA; a 78 Folk album Daver missed, and a Granz-era surprise (who knew Al Hirt got a DSM look-in?); an illustration from a children's songbook (more rabbits!) showing the artist's simpler side, along with a drawing of Jelly Roll so detailed and distinct from the artist's usual sketchy, often surreal style, that it might stand in for those long-forgotten Time covers too; plus some other LP jackets missing from one source or the other (like the beautiful scene up top  of Bud Powell taking a piano lesson from Mary Lou Williams, which really did happen).

of Bud Powell taking a piano lesson from Mary Lou Williams, which really did happen). The world of record collecting would be immeasurably more bland and boring without David Stone Martin's Jazz graphics. (And a tip of the hat to Norman for turning him loose.)